Last semester we started playing Churchill in our wargaming class at ISM University of Management and Economics in Vilnius, Lithuania. This article looks at how the game can contribute to the broader learning objectives in social sciences’ studies.

One of the challenges in teaching wargame design in a civilian context is finding games on topics that students have learned about. Of course, discussing games specifically focused on the military also works, but it is important to connect wargaming to issues that have been discussed in other classes. This makes it easier to connect a game with real processes and to learn to read the game as a model of the simulated topic. A game with a familiar topic also helps to reduce time needed to get into the game and is more intuitive to play. As classroom hours tend to be quite short, it is an important advantage.

Churchill addresses exactly these challenges. Students know the general story of World War Two well, and they have certainly learned about at least the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam conferences. I don’t think there ever was a final high school history exam that didn’t include questions on at least one of them. Yet, familiarity with the topic alone is not enough to make sure that the game will be a good fit for the classroom.

So, why does Churchill work and what can it teach? I’ll try to answer this question by addressing several smaller ones. Who are the players? What are their decisions and incentives? Where do they find themselves? What can they change?

Who are we?

The key characteristic of Churchill is negotiation structure. Instead of leaving it to free-form discussions among players, this game places negotiation at the centre of rigid mechanics. It achieves several things:

- Puts focus on the politics of the end of WW2 and the post-war order.

- Gives personalities the centre stage.

- Defines player agency by giving them the clear roles as the head of the US, UK, and USSR delegations.

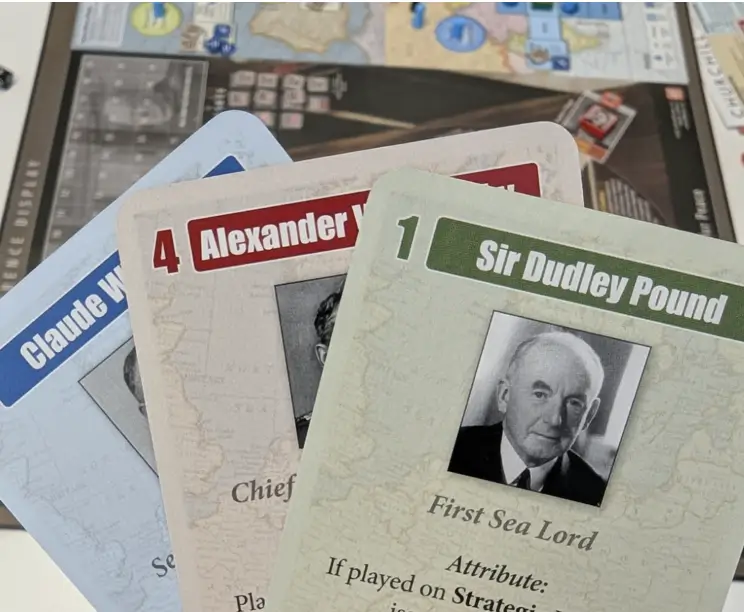

Stepping away from the kinetic fight and looking at the negotiations provides students with a setting that is familiar to them, from the International Relations or History classes. The delegation staff personalizes that setting – from the leader to each staff member, you are affected by what the government sent to the conference, with each strength and weakness that the delegation members bring. Variation among the three factions also helps to better understand the logic of each side better through the constraints imposed on the player.

From the educational perspective, such setup makes it easier for students to engage with the game model as active participants. In our wargaming class, we learn to read games as an alternative way to model social reality. In most research models students have learned before this course, agent behaviour is defined by assumptions (e.g. rationality), payoff maximization (e.g. in game theory), or more elaborate rules of behaviour (e.g. in agent-based models). Games, however, give the model agent freedom within the boundaries of the rules.

Certainly, there are constraints and incentives, but you have people making actual decisions. For students, this is a new way to look at models, and it is important to introduce it carefully. Churchill’s focus on personalities makes this entry easier – it is clear who we are, when we play, and what dilemmas we are facing.

What do we care about?

So what are those decisions and what do we care about in the game?

Churchill puts forward specific issues as the central to the simulated conferences. They range from production to accumulation of political influence to nuclear weapon research. Nonetheless, most of them affect progress and influence in the European and the Pacific theatres of WW2. On the one hand, it seems to be binding – we do not see the civilians and the local populations. But what the big three care about is first and foremost winning the war, even if focusing production on the military implies a tension between it and civilian spending. On the other hand, it focuses the game narrative well and helps players to engage more strongly with the economics of war.

Since the beginning of the game, the players know that they can win the war. Therefore, the second important question that they face is – what comes after. Here, the answer is centred around Global Issues.

Self-determination or colonialism? Free Europe or Spheres of Influence? United Nations or the presence of Communist Cadres?

These are the questions that defined the post-war order. Even though the game provides a rigid rule structure to these issues, they can be used to encourage student debate as well. Why did one side prefer one option over the other? What was the effect of the historical outcome?

Of course, there are other issues at stake. The race for the A-bomb. Theater Leadership struggles. The need for strategic materials. Nonetheless, the decision space remains quite locked. In the context of the classroom, it is a very positive trait. Within the limited time you have, you can teach the game more easily and focus the discussion on the key topics that the game highlights.

What if..?

Churchill includes thirty conference cards to depict ten conferences. So, you get a historical version and two counterfactuals. Each conference card affects the players and the military or political game situation. Why is this important to consider? Our high school curriculum puts emphasis on the conferences in Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam (and for a good reason). However, it leaves the others aside and shows the whole negotiation process as a discrete rather than continuous effort.

The inclusion of alternative versions of the conferences also opens the floor for discussion. Why did they go the way they did? What could have happened and what could have been the results of those differences? From the teaching perspective, what these alternative narratives provide is a demonstration of exogenous effects on a game-based model of reality. You change an external variable (as the card text does not depend on players’ actions), and the model may produce different incentives, different behaviours, and different results.

Which leads to the question of other counterfactuals. The game gives space for the players to experience what if scenarios, where some model elements depend on details such as Stalin’s paranoia or Churchill’s heart issues. It helps to achieve two objectives. First, such details add variability to the framework. Second, they add to the thematic immersion and provide players uncertainty and excitement about what can happen.

The end state of the game, which may be historical or not, can also focus a post-game debrief on how we arrived there. The discussion here can be structured both around the narrative and around the model – what led the players to the outcome they got. This latter part of the discussion is very helpful to addressing one of our learning outcomes – understanding how a game works as a model and how it reflects reality.